Pure Subdural Hemorrhage Caused by Internal Carotid Artery Dorsal Wall Aneurysm Rupture

Article information

Abstract

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with altered mentality. The patient was diagnosed an internal carotid artery (ICA) dorsal wall aneurysm leading to acute subdural hemorrhage (SDH) without occurring subarachnoid hemorrhage and/or internal parenchymal hemorrhage. An aneurysmal neck clipping and hematoma evacuation were performed at once. A pure SDH by ruptured aneurysm is unusual, but it is important to consider it if a SDH patient has no other medical history.

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial aneurysm rupture usually presents as a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), often in combination with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and/or intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH).1)9) Occasionally, aneurysm rupture may accompany acute subdural hemorrhage (SDH).15) However, pure SDH occurring without detectable SAH is very unusual.2)13) We report a case of pure SDH secondary to internal carotid artery (ICA) dorsal wall aneurysm rupture.

CASE REPORT

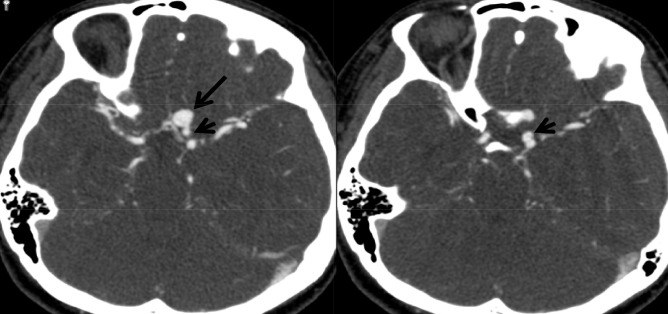

A 37-year-old female presented with altered mentality. Upon arrival, she could not open her eyes and exhibited trace muscle contraction to painful stimuli. There was no external mark of injury and both pupils were dilated and fixed. Brain computed tomography (CT) performed at the emergency room revealed acute SDH compressing the left hemisphere extensively. The maximal thickness of SDH was measured to be 15 mm, causing 14 mm midline shifting to the right side and transtentorial herniation (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of SAH or ICH. However, after taking past medical histories from her parents, we found out she had been diagnosed as having an intracranial aneurysm. The patient had undergone digital subtraction angiography (DSA) one month ago at other institute. Coil embolization had been recommended after DSA, but the patient and parents were reluctant to accept the risks related to preventive treatment.

Brain CT shows acute subdural hemorrhage causing 14 mm midline shifting and transtentorial herniation in the absence of subarachnoid hemorrhage. CT = computed tomography.

Subsequent CT angiography obtained at the emergency room demonstrated an aneurysm arising from the distal ICA (Fig. 2). But, it was not clear whether the aneurysm was related to the SDH or not. We decided to evacuate the SDH immediately and requested her parents to bring a copy of DSA images. Under general anesthesia, a large fronto-temporo-parietal craniotomy was performed. A small skull defect close to the Kocher's point was found, that was later found to be the vestige of external ventricular drainage performed 20 years ago for unexplained spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage. The dura mater was widely opened and the possible sources of SDH were carefully investigated with removal of hematoma. There was no evidence of cortical SAH, brain contusion, or bleeding in the cortical arteries as well as bridging veins. However, when we explored the orbitofrontal cortex, thick clots covering the gyrus rectus and the medial orbital gyrus was noted and was presumed to cover the source of SDH.

CT angiography demonstrates an aneurysm (arrow) originating from the left internal carotid artery in close proximity to the anterior communicating artery complex. CT = computed tomography.

At that time, the patient's parents brought DSA images demonstrating a large right-angled aneurysm arising from the dorsal wall of the left internal carotid artery (Fig. 3). The size of aneurysm was measured to be 12 mm in maximal diameter with a 5 mm-sized neck. To clip the aneurysm neck first, the carotid cistern was opened and the ICA was exposed under the microscope. There was no SAH in the carotid cistern and the elongated aneurysm neck ran beneath the optic nerve (Fig. 4). Direct neck clipping was performed without too much difficulty and the thick clots covering the aneurysm dome was removed (Fig. 5). The aneurysm dome breaking through the gyrus rectus was confirmed and the presumed ruptured point that caused pure SDH was embedded within the clots. She regained her consciousness two weeks after surgery and is currently undergoing rehabilitation treatment.

An operative view of rotational 3D angiography shows a large right-angled aneurysm arising from the dorsal wall of the left internal carotid artery.

An intraoperative photo reveals the AN, ICA, ON, and thick clots covering the aneurysm dome. Note that there is no evidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage around the aneurysm neck (arrowheads). AN = aneurysm; ICA= internal carotid artery; ON = optic nerve.

DISCUSSION

The most common pathogenesis of acute SDH is traumatic disruption of a bridging vein draining into a venous sinus.15) Other less common causes include all conditions of non-traumatic SDH, among which are coagulopathies, vascular malformations, intracranial hypotension, cerebral venous thrombosis, brain neoplasm, inflammatory conditions, and so on.2) Reported incidence of acute aneurysmal SDH varies from 0.5 to 7.9%.14)17) However, pure subdural hemorrhage caused by intracranial aneurysm is extremely rare.10)16)

We describe a case of ruptured ICA dorsal wall aneurysm of pure subdural hematoma. Gong et al.4) reviewed 40 similar cases of pure subdural hematoma caused by intracranial aneurysm have been reported since 1980. The site of aneurysm included ICA-posterior communicating artery (PcomA : 16 cases) MCA (10 cases) anterior communicating artery (AcomA : 6 cases) distal ACA (4 cases). Other cases involved ICA bifurcation and ICA adjacent to carvenous sinus. Now we present the first case that ICA dorsal wall aneurysm rupture presenting a pure SDH.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain pure SDH caused by rupture of aneurysm : 1) minor aneurysmal leakage make an aneurysm adhesive to the arachnoid membrane with a final bleed occurring into the subdural space.3)7)10)12) 2) a hemorrhage under high pressure may lead to pia-arachnoid rupture and extravasation of blood in to the subdural surface.3)5)7)8)3) intracerebral bleeding may rupture the cortex and tear the arachnoid membrane.5)6) 4) enlargement of the intra-cavernous aneurysm could erode the wall of the cavernous sinus.8)16) 5) an aneurysm located in the subdural space may cause subdural hematoma directly.6)11)

By the first mechanism, there were usually episodes of aneurysm rupture. Patients had symptoms like headache before the main episode. In our case, the patient didn't have any history. Unlike the second mechanism, we found out an aneurysm dome had penetrated pia mater directly. The fourth, fifth mechanisms are inappropriate for our case. At last, our case might be similar to the third mechanism.

Some differences in CT appearance between SDH by a ruptured aneurysm and that of traumatic origin have been suggested.6) Weir et al.17) reported that a subdural hematoma secondary to a ruptured aneurysm was unilateral, hyper-dense, and convex or triangular over the lower sylvian fissure, whereas traumatic subdural hematoma was more likely to be of mixed, isodensity or hypodensity, and might be bilateral or lentiform as well as cresentic. In our case, CT scans showed a typical sign described above.17)

In our case, we diagnosed a SDH by rupture of aneurysm easily, because we checked out her history. But, it may be difficult to diagnose a pure SDH caused by aneurysm. Recently, 3-dimension CT angiography may helpful to diagnose this situation and require little additional time.5)

CONCLUSION

A pure SDH may be caused by an intracranial aneurysm rupture. This condition is rare, it may lead to delay in diagnosis. So, aneurysm rupture should be considered, if a patient presents pure SDH without history of trauma or coagulopathy. A CT angiography and/or digital subtraction angiography should be performed and suitably treated if aneurysm was found.

Notes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.