Neurological Deterioration after Decompressive Suboccipital Craniectomy in a Patient with a Brainstem-compressing Thrombosed Giant Aneurysm of the Vertebral Artery

Article information

Abstract

We experienced a case of neurological deterioration after decompressive suboccipital craniectomy (DSC) in a patient with a brainstem-compressing thrombosed giant aneurysm of the vertebral artery (VA). A 60-year-old male harboring a thrombosed giant aneurysm (about 4 cm) of the right vertebral artery presented with quadriparesis. We treated the aneurysm by endovascular coil trapping of the right VA and expected the aneurysm to shrink slowly. After 7 days, however, he suffered aggravated symptoms as his aneurysm increased in size due to internal thrombosis. The medulla compression was aggravated, and so we performed DSC with C1 laminectomy. After the third post-operative day, unfortunately, his neurologic symptoms were more aggravated than in the pre-DSC state. Despite of conservative treatment, neurological symptoms did not improve, and microsurgical aneurysmectomy was performed for the medulla decompression. Unfortunately, the post-operative recovery was not as good as anticipated. DSC should not be used to release the brainstem when treating a brainstem-compressing thrombosed giant aneurysm of the VA.

INTRODUCTION

Decompressive suboccipital craniectomy (DSC) is useful for releasing infratentorial pressure in the posterior fossa and is performed in patients with Chiari malformation, cerebellar stroke, or infratentorial traumatic brain injury.1)7)8) This technique allows not only the cerebellum, but also the brainstem, room to expand without being squeezed in the posterior fossa. However, the surgery should be performed with careful consideration of the risks and benefits. Here, we report a case of neurological deterioration after DSC in a patient with a brainstem-compressing thrombosed giant aneurysm of the vertebral artery (VA).

CASE REPORT

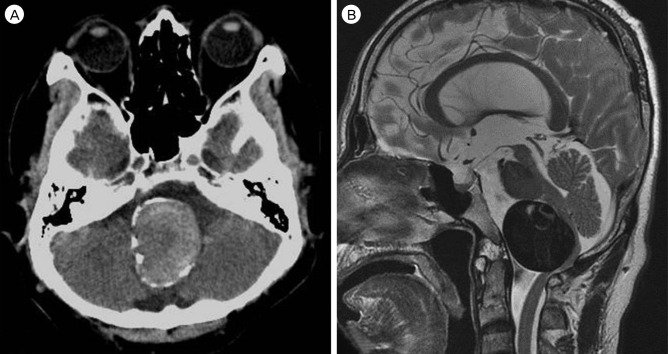

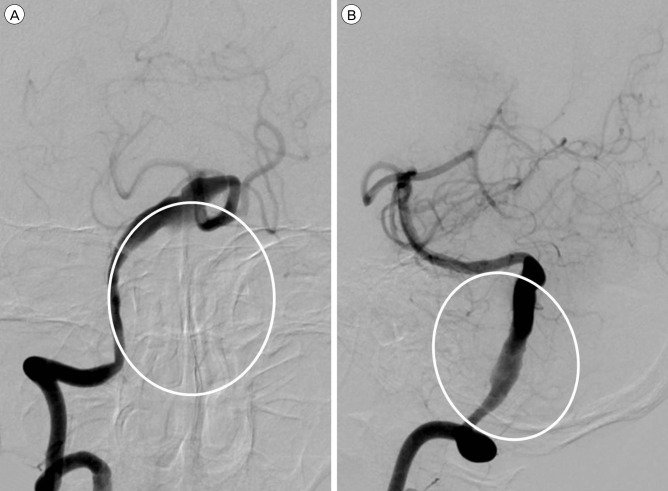

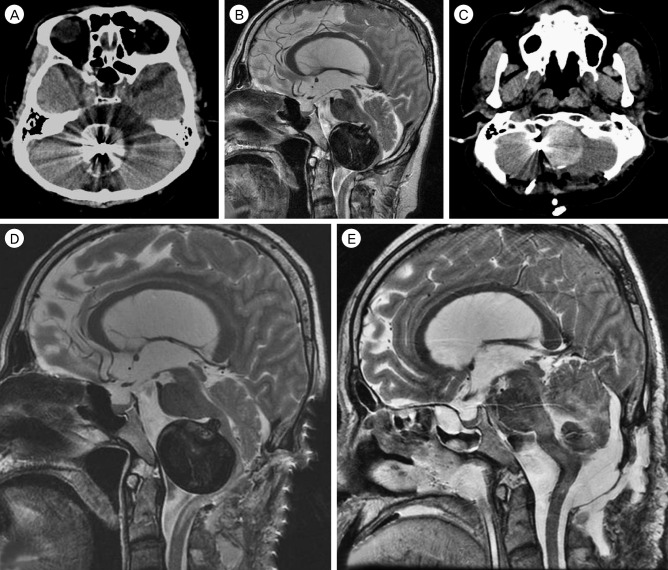

A 60-year-old male harboring a thrombosed giant aneurysm (about 4 cm) of the right VA presented with quadriparesis. His head computed tomography (CT) showed surrounding calcification of the aneurysm wall (Fig. 1A), and magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed that his medulla oblongata was squeezed between the aneurysm and the occipito-cervical junction (Fig. 1B). Cerebral angiography showed fusiform-like dilatation of the right VA due to the thrombosed sac. The real contour of the aneurysm is indicated by a white circle in Fig. 2. Because the left VA was healthy and showed a good patency, we treated the aneurysm by endovascular coil trapping of the right VA and expected the aneurysm to shrink slowly. After treatment, complete occlusion of the aneurysm was successful and the patient's symptoms improved. After 7 days, however, he suffered aggravated symptoms, including quadriparesis, respiratory disturbance, and decreased mentality. Follow-up MRI revealed that the aneurysm ad grown due to internal thrombosis and that medulla compression of the aneurysm was aggravated (Fig. 3A, B). In order to improve the medulla compression, we decided to perform DSC with C1 laminectomy (Fig. 3C). After the third post-operative day, unfortunately, his neurologic symptoms were more aggravated to complete quadriplegia and weaker respiration compared to his pre-DSC state. Post-DSC MRI showed more angulation of the medulla posteriorly with dense high signal changes from the medulla to the upper spinal cord compared to pre-DSC MRI (Fig. 3D). Despite of conservative treatment, neurological symptoms did not improve, and microsurgical aneurysmectomy was performed for medulla decompression (Fig. 3E). However, postoperative recovery was not as good as anticipated after the operation. He was discharged as modified Rankin Scale 5.

Initial radiographic findings. (A) Computed tomography showed surrounding calcification of the aneurysm wall and (B) magnetic resonance image revealed that the medulla oblongata was squeezed between the aneurysm and occipito-cervical junction.

Cerebral angiography showed fusiform-like dilatation of the right vertebral artery due to the thrombosed sac. The real contour of the aneurysm is indicated by a white circle. (A) Antero-posterior view. (B) Lateral view.

Follow-up radiographic findings. (A) and (B) The aneurysm size was increased due to internal thrombosis after endovascular trapping of the right vertebral artery, medulla oblongata compression of the aneurysm was aggravated. (C) Decompressive suboccipital craniectomy (DSC) with C1 laminectomy was performed. (D) Magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed more angulation of the medulla oblongata posteriorly with dense high signal changes from the medulla to the upper spinal cord compared to pre-DSC MRI. (E) Microsurgical aneurysmectomy was performed for medulla decompression.

DISCUSSION

In the present case, neurological deterioration was experienced after DSC to treat a brainstem-compressing thrombosed giant aneurysm of the VA, suggesting that this clinical situation requires very careful pretreatment planning. DSC does not appear to have been a good choice for decompression of the mass effect. Instead, it may have aggravated and worsened the mass effect, because the aneurysm compressed the brainstem from its anterior aspect and made angulation posteriorly with a further stretching of the medulla and the upper spinal cord compared to the pre-DSC state.

A giant aneurysm of the vertebral artery is rare, occasionally associated with thrombosis, and may present with symptoms and signs of the brainstem compression.2)6) Thrombosed giant aneurysms are difficult to treat and their outcomes are hard to predict.3)4)6)11) Various treatment modalities have been tried for such an aneurysm, such as direct clipping of the neck of the aneurysm with a neck remodeling technique, trapping of the parent artery either by microsurgical clipping or endovascular coiling with/without bypass surgery, aneurysmectomy after trapping of the parent artery, and, recently, flow-diversion. At the time this patient needed care, the flow-diversion technique was not available in our country. Trapping of the parent artery with/without bypass surgery is usually thought to be one of the most preferred methods, but the results of such treatment are always unpredictable. In the present case, the contralateral VA showed very good patency, and so we treated the patient with the trapping of the ipsilateral VA by endovascular coiling, expecting that the aneurysm to shrink slowly.

Usually, DSC is useful to release infratentorial pressure in the posterior fossa. The main purpose of DSC is to release posterior brainstem compression from a swollen cerebellum. In the case of a thrombosed giant aneurysm, however, the mass compresses the anterior aspect of the brainstem so that DSC is not an effective option for such a case. After performing DSC, in the present study, we experienced more stretching and kinking of the medullar and the upper cervical spinal cord between the superior margin of DSC and the C2. The mechanisms resembled worsening neurological symptoms and signs seen when treating an ossified posterior longitudinal ligament patient with cervical kyphosis by posterior cervical laminectomy or laminoplasty. In such a patient, an optimal shift of the spinal cord cannot be achieved by posterior decompression. Additionally, a lesion will remain that is compressing the spinal cord from the anterior aspect.9)10)12)

In retrospect, we should have performed the microsurgical aneurysmectomy as an initial treatment option rather than endovascular trapping of the VA, because initial CT showed the aneurysm wall was calcified all around. The calcified wall of the aneurysm would not shrink after the trapping of the parent artery.5) Regretfully, we should not have performed DSC after the aneurysm size grew due to internal thrombosis and the medullar compression of the aneurysm was aggravated. As mentioned above, DSC for such a lesion was not effective at all.

CONCLUSION

DSC should not be considered to release the brainstem when treating a brainstem-compressing thrombosed giant aneurysm of the VA. Appropriate planning of the initial treatment approach is essential. DSC could aggravate and worsen the mass effect of a brainstem-compressing aneurysm.

Notes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.