INTRODUCTION

Intracranial dissections commonly present as ischemic stroke and as hemorrhagic stroke. Reports suggest that only 25% of vertebrobasilar dissections and 15% of internal carotid dissections present with hemorrhage.5) The plane of dissection is an important predictor of presentation. In patients presenting with ischemia, the dissection is usually noted between the internal elastic lamina and the tunica media.2) In hemorrhagic cases, the dissection plane extends transmurally from the lumen of the artery through the tunica intima and media to the adventitia.4)

In this case report, we present a case of simultaneous development of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke due to an intracranial artery dissection.

CASE REPORT

History

A 39-year-old male patient with the chief complaint of left-side motor weakness arrived at the emergency department. He was alert with no unusual medical history or ongoing medications. Blood pressure was normal, and results of laboratory investigation did not indicate coagulation abnormality or other specific findings. The patient began to show symptoms nine hours before arrival at hospital.

Examination

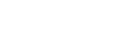

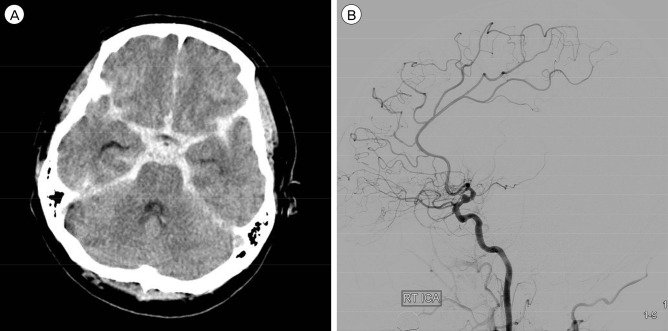

Brain computed tomography (CT) and brain CT angiography taken at our hospital showed a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the right sylvian fissure and a right proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion (Fig. 1A, B). A series of brain magnetic resonance images (MRIs) and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed an acute cerebral infarction in the right striatocapsular area due to proximal right middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion (Fig. 1C, D). The patient had both ischemic stroke and SAH. No salient lesions that might be considered a cause of SAH were observed. Therefore, considering it a large-artery ischemic stroke, we established a treatment plan. Because more than nine hours had passed since the patient's symptoms developed, we decided that medical treatment through dual antiplatelet medication (aspirin 100 mg daily, clopidogrel 75 mg) would be better for the patient than any other treatments.

Operation

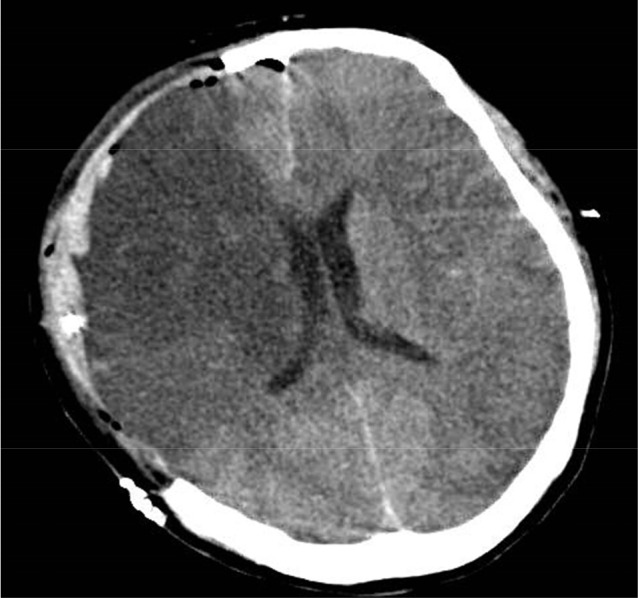

On the fifth day after admission, he had an episode of tonic-clonic seizure and brain CT after seizure showed increased SAH at the basal cistern and both sylvian fissures (Fig. 2A). DSA showed a lesion, apparently a dissecting aneurysm (DA), in the right supraclinoid internal carotid artery (ICA), that had not been visible earlier (Fig. 2B). Due to the patient's stuporous consciousness level, it was impossible to perform a balloon test occlusion. However, trapping of the lesion in the ICA was considered viable based on the “Allcock test” and “Matas test” results. Thus, internal coil trapping was performed on the right supraclinoid ICA lesion. Subsequently, lumbar drainage was performed, and his consciousness level improved to drowsy.

On the 11th day, the follow-up brain MRI showed that the size of the cerebral infarction had increased, although the patient's condition did not worsen until the following day, reverting to the stuporous consciousness level. CT scans showed an increase in the size of the cerebral infarction. Therefore, we performed a decompressive craniectomy.

Postoperative course

On the day of the decompression, his pupil size was normal. The next day, his pupil size had increased with no light reflex. The brain CT showed low density in both hemispheres due to vasospasm (Fig. 3). The patient was diagnosed as brain dead, followed by organ donation and death.

DISCUSSION

DAs of intracranial vessels are more common in the posterior circulation (80%) than in the anterior circulation (20%). DAs are associated with cystic medial necrosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, moyamoya disease, atherosclerosis, homocystinuria, and intimal fibroelastic thickening.4)

DAs can lead to severe morbidity and mortality, and cause both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. A dissection between the internal elastica and the media typically presents as an ischemic stroke accompanied by occlusion of the affected portion, and a subadventitial dissection between the media and the adventitia usually presents as hemorrhage.3)

The following hypotheses may account for the relevant mechanism. Significant hemodynamic stress on the vascular wall causing simultaneous or serial occurrence of subintimal and subadventitial dissections is one possible explanation. Others have suggested that the expansion of the wall by dissection leads initially to arterial wall perforator ischemia, which can be followed by a transmural dissection and rupture of the wall.1) Ischemic stroke followed by a hemorrhage is rare, and occurrence of both simultaneously, as in these reported cases, is also rare.

In the case, despite careful observation for any possible lesions causing SAH, no relevant characteristics were detected. Due to the rarity of anterior circulation dissection, clinicians may overlook or fail to notice it. Nevertheless, in this case, it was difficult to find any definite lesions in a retrospective observation. Still, we might have failed to diagnose the dissection at first because we did not pay enough attention to supraclinoid ICA dissection, by completing the examination without checking the 3-dimensional image of the initial DSA.

Surgical treatment for a ruptured DA includes proximal clipping, or trapping, and clipping with or without revascularization. Alternatively, endovascular strategies can be used, including proximal parent vessel occlusion, internal coil trapping, stent-assisted coil embolization, stent-only therapy, covered stent placement, or any combination thereof.7) More recently, the deployment of a flow diverter stent has been used.6)

In the case, in connection with the simultaneous development of ischemic stroke and SAH implying a severe dissection, we first focused on only the right proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion, and administered a dual antiplatelet treatment. However, when the exact cause of SAH is not known, the antiplatelet treatment seems to not be helpful before cause is determined. We thought the cause was a large-artery atherosclerotic ischemic stroke, but it finally was diagnosed as ischemic stroke due to a DA. DA itself carries a high risk of causing re-bleeding. The medication might be suspected of increasing the re-bleeding risk.

In addition, when the simultaneous onset of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke is attributable to dissection, this implies a severe development of the dissection, increasing the likelihood of recurrent infarction and re-bleeding. Hence, more proactive examination and treatment are required.

CONCLUSION

Dissection of the intracranial artery presenting with simultaneous development of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke is rare and thus difficult to diagnose. However, consideration and suspicion of simultaneous development of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke is important to prevent unfavorable results. In the same vein, appreciation of the natural history of intracranial artery dissection and development of individualized treatment plans is necessary.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print